whitehot | October 2008, Interview with the curators of Der Blind Fleck

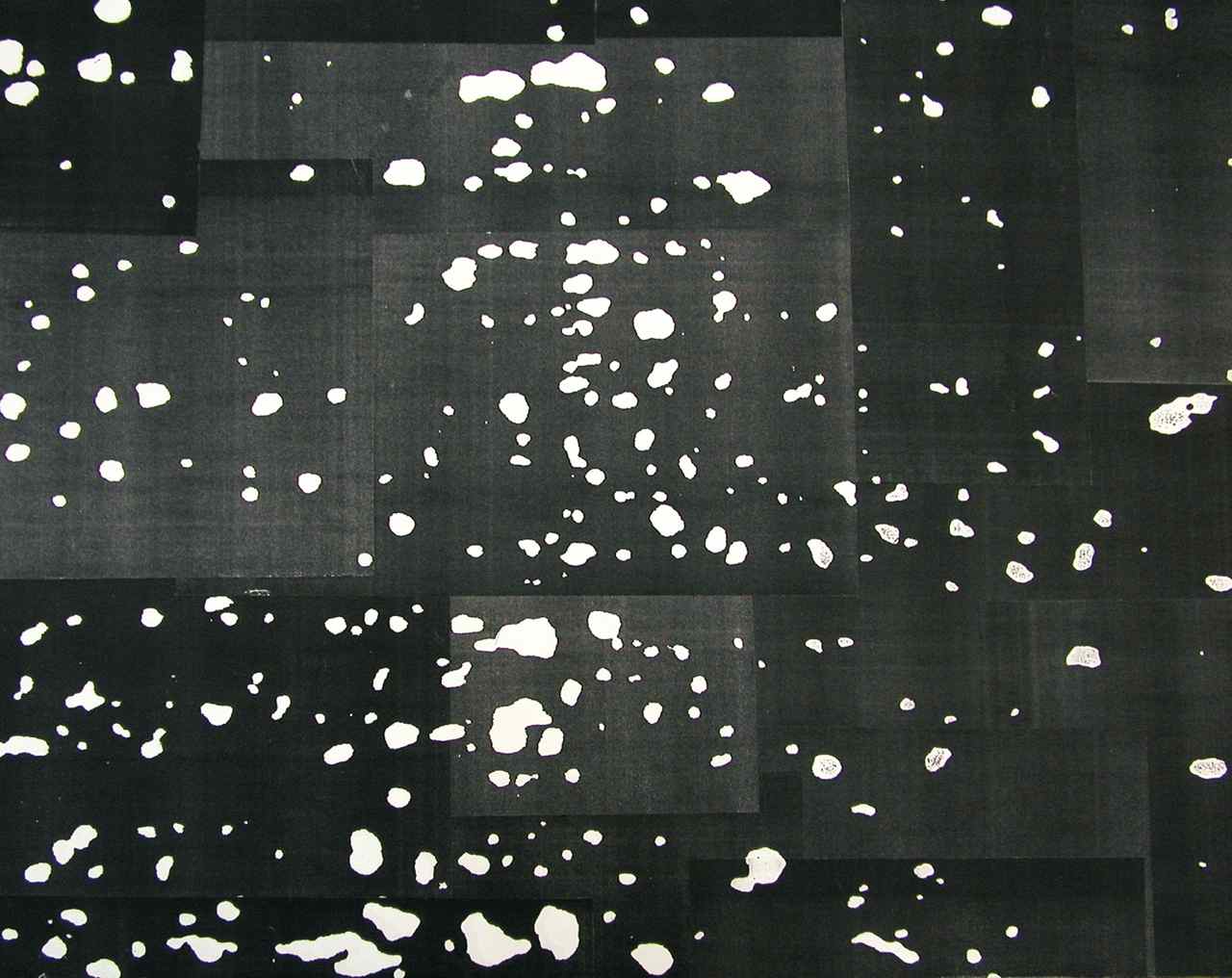

Ilka Meyer

1001, 2004

360 x 660 cm

Installationsansicht

Courtesy of NGBK and the artist

Foto: Ilka Meyer

© Ilka Meyer

Jaime Schwartz Interviews curators Lith Bahlmann and Anke Hoffman

Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst

Der Blind Fleck

Through October 19, 2008

Recently

I discovered the past and present works of artists from the Balkans and

immediately decided I wanted to head anywhere in the vicinity. The

works of many of these Balkan artists, such as Luchezar Boyadjiev and

Slovene collectives Irwin and NSK, investigate the dynamic interactions

of cultural and visual contexts in regards to urban space and the

overlapping identities Eastern Europeans occupy. What interested and

inspired me in the work coming out of such nations was how these

artists were dealing with the abrupt transitions going on around them;

Changing from former communist countries into part of the European

Union all the while negotiating new recognition from the West. I wanted

to see how artists were reacting to these changes and how these changes

affected both the personal and political memories of these nations.

I

think we can all agree that at some point almost every Government has

tried to cover up its past mistakes through creating new connotations

to physical sites, by renaming or reconstruction, or through

repositioning the collective consciousness of historical phenomenon.

However, Governments are not the only ones with an interest in

reshaping the memories of the not so pleasant past. What about people?

How do we personally play a role as well in the dichotomies of

remembering and forgetting, both collectively and individually?

Well,

I didn’t wind up in Slovenia or anywhere else in the newly coined

“Western Central Europe” (i.e. the Balkans) but here in Berlin I did

find a gallery that was also interested in exploring these issues.

The exhibition Der Blind Fleck

(the blind spot) hosted by the Neue Geselleschaft fur Bildende Kunst

(NGBK) uses the blind spot, an optical phenomenon, to explore the

social and political dialectic of memory and forgetting. A blind spot

is produced by the insensitivity of the retina region of our eye,

creating a temporary inability to visually access everything in our

surroundings. The artists in this exhibit have used the blind spot as

metaphor for the way both cities and people rebuild or abandoned in

order to make tragedy and trauma inaccessible and unseen. The

exhibition displays the power of both physical and psychological

spaces, examining how the human mind can also create blind spots

through our ability to forget or selectively remember.

For me

the exhibit brought up some larger questions and I was fortunately able

to address these with the curators Lith Bahlmann and Anke Hoffman.

Jaime Schwartz:

What is the significance (if any) of displaying this show here in

Berlin? Do you think the unification of Germany is somehow an

example (good or bad) of a city remembering/forgetting the past, or

somehow parallel to the experiences of those living in former communist

states?

Lith Balhmann: Well, in the

current discourses about the politics of remembrance and memory,

Germany is still a country post-Auschwitz: all political events are

somehow related to this dark side of Germany’s past and are subject to

interpretation under this historical and political parameter. Berlin

itself is based on the past always relating to great narrations of

progressiveness and victory in the sense of grand triumph and success.

Monuments such as the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate are no longer

manifestations of power but have since transformed into physical

symbols of memory and their connotation has changed and will continue

to change.

However, our

thematic approach to the exhibition is not exclusively politically

motivated. We didn’t try to draw comparisons concerning questions about

the coping with history in the post-socialist EU-states. The exhibition

title Der Blinde Fleck serves us in our curatorial

investigations primarily as a metaphorical vehicle allowing us to

widely associate the very different aspects of the mechanisms and

meanings of forgetting, selective disremembering and memory repression.

The exhibition shows a selection of international artistic positions,

concerning not only the phenomenon of reality, but also illuminating

varied social discourses. We chose works that concern issues of

obliteration and reduction purely aesthetically and works that actively

question the human perception of blind spots, for example, the

internet-platform Zone*Interdite by the Swiss artists Chrisoph Wachter and Mathias Jud.

Anke Hoffman:

For me, the significance of the exhibit being displayed in Berlin is

similar to the predicament of almost every society that has experienced

a political (and ideological) transformation. The significance being

that architectural symbols and landmarks in a City are constantly being

re-interpreted according to the perspective of the current political

power. This change of perspective evokes specific historical stories

and historical contexts in regards to the ruling power. This has

happened in Berlin after the re-unification, and in many other former

East European cities that are still in transition. For example in

Berlin, street names have been changed, the city has been "cleansed" of

former "heroes" without questioning and the much discussed dismantling

of the former Palace of the Republic which attempts to negate the 40

year history of a communist/socialist run country with all its

ambivalent decisions and ideologies.

So in this example, yes, there is a certain motivation to make such an

exhibition about these topics here in Berlin, although as Lith stated,

we consider this exhibition to have a wider theme than only the

political and historical issues of a national culture. Nevertheless,

you can read something about the dealing with history in different

transforming cities in the work of Hörner/Antlfinger, who researched

individual coping strategies within Sofia, Bulgaria, and also in the

work of Hito Steyerl, about the former ideological history of the

Yugoslavian "Idea".

JS: Do you think

there is a difference between not forgetting and remembering?

Does one have a more positive connotation? And how are the

artists playing with the dichotomy?

LB:

I think there is no forgetting without remembering and no remembering

without forgetting, however, it is difficult to say which one is

politically more dangerous since both options have the tendency to

obliterate the past whether through exclusion or through the attempt to

control and predetermine how these acts should be introduced into the

cultural memory of today and tomorrow. In this context, forgetting has

a more negative connotation. However, there are also positive aspects

concerning forgetting which can be seen in the large-scale installation

Allee der Schlaflosigkeit (Avenue of Wakefulness) from Berlin based artist Klaus Weber and the series of paintings from Albrecht Schäfer.

The Avenue of Wakefulness

is an architectural model filled with blooming Angel’s Trumpets whose

fragrance is said to have a narcotic effect. Weber’s idyllic setting

provides a place of intoxicated transgression of the existential

boundaries of time and space temporarily withdrawn from reality that is

dominated by control mechanisms and security concepts. When one enters

this installation, there is a temporary loss of control and loss of the

self that becomes a Dionysian experience of “forgetting oneself”. This

can ultimately be read as the antithesis of the Apollonian impulse

towards harmony and control. Albrecht Schäfer, shows in his work that

selectively disregarding redundancies can lead to an active form of

forgetting and finally to a cleansing process. In his piece The Sun, 4.8.2007

Schäfer changes every single page of an edition of a selected English

tabloid into a monochromatic grey surface, effacing the object’s

significance, leading to a white noise of information.

AH:

The only thing worse than losing your mind ... is finding it again, to

paraphrase director David Cronenberg and the introductory quote from

film historian Matthias Wittman’s essay in the exhibition catalogue.

There are definitely a lot of positive aspects and appeal to

forgetting. Forgetting helps us to overcome some of our everyday

feelings of pain and frustration. However, forgetting is a virulent

part of these rather psychological and social behaviors.

Beside the works of Weber and Schäfer we have also put this method to

work in the exhibition design itself. You enter and are confronted with

rather sensual and abstract works and then further inside you come

towards the issues of politics, history and research. Once you have

walked through the entire exhibition you enter Weber’s Avenue of Wakefulness

and find yourself in a idyllic garden setting of bumble-bees and

wonderful smelling flowers, allowing you to relax and almost forget

what you have just heard and seen...

Klaus Weber

Allee der Schlaflosigkeit, 2005

Installationsfotos

Courtesy Andrew Kreps Gallery and NGBK

© Klaus Weber

JS:

Do you see people or places having an advantage in the not

forgetting/remembering dichotomy? Do you feel on is more

successful/holds more weight than the other? For example the

video Piece Journal # 1 - An Artists impression vs. the photographs of

Richard Chutz and the video of Nina Fisher and Maroan El Sani.

LB:

I see those three pieces engaged in the forgetting of history in very

different ways. I feel they follow different thematic approaches and

thus are open to different thematic discourses. In this sense the whole

exhibition possesses no narration but naturally the works correlate to

each other and that is of course intended and desirable in a group

show.

The photographic series Jetztzeit

(Realtime) from Richard Schütz operates in a fascinating realm

in-between a fictionalized and documentary-style representation of

history. His images question the consequences of fictionalizing history

and how this has now become one of the most popular forms of media

entertainment. The photograph from his series titled Ausblendung

(Fade Out) shows the Palace of the Republic behind a casing-wall,

clearly referencing the present political need to erase contemporary

evidence of German state socialism by eradicating its symbols and at

the same time it’s like a historical déjà-vu to reconstruct the

Prussian city palace. This process exemplifies the present relationship

between West Germany and East Germany.

Hito Steyerl’s film rather deals with subjective means of giving

testimony and individual reconstruction of history that exist for the

multiethnic citizens of the former Yugoslavia. These memories consist

of very different images, exemplifying that there is not only one

single narration.

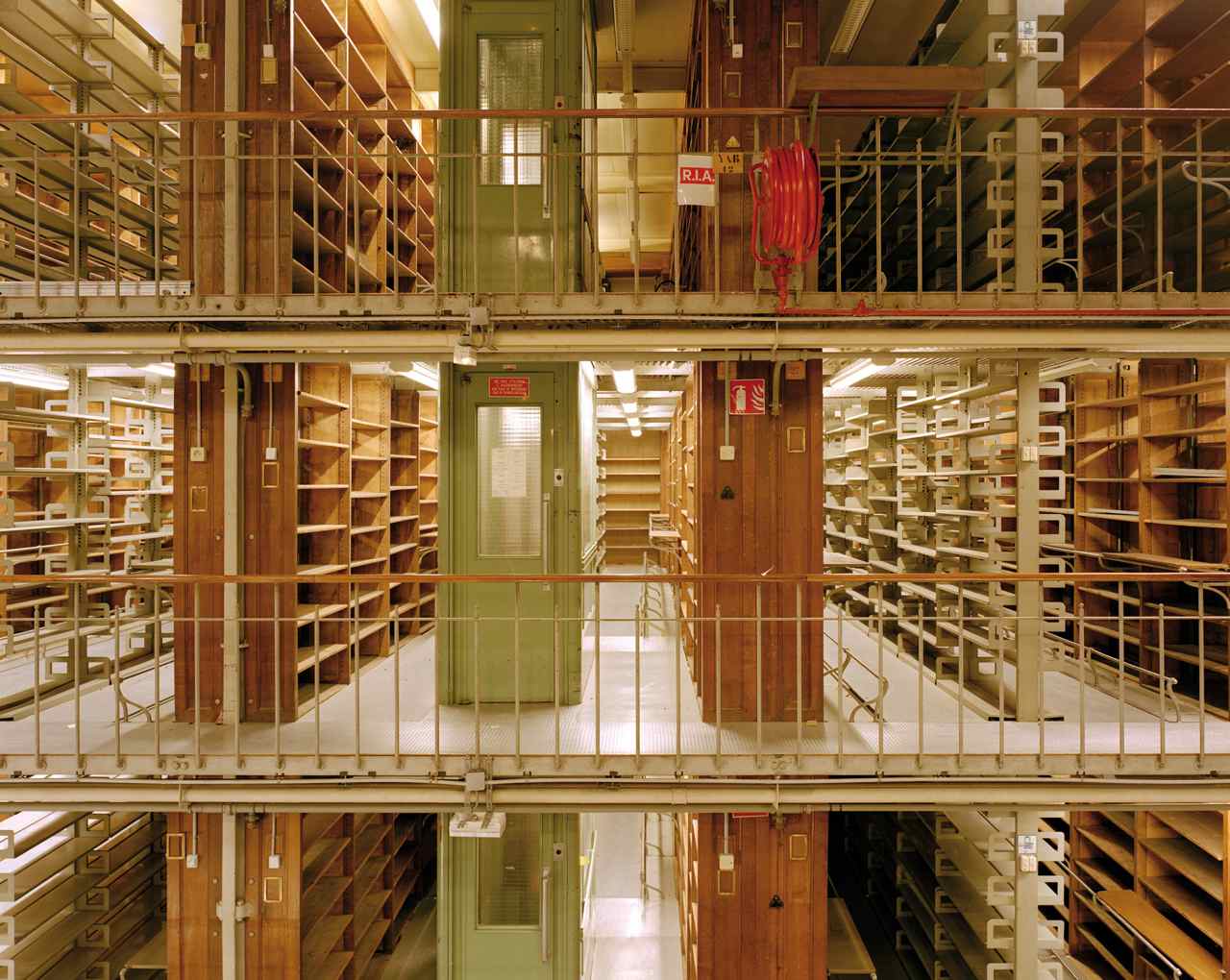

In Nina Fischer and Maroan el Sani’s film Toute la memoire du monde-BNF I

deals with the loss of traditional knowledge spaces in today’s

internet-based world. Their film addresses how we are currently

confronting an information overload while simultaneously experiencing

an increase of forgetting. As if the over saturation of information is

creating yet another blind spot.

Richard Schütz

Ausblendung, 2003

60 x 90 cm

Courtesy of NGBK and the artist

© Richard Schütz

Nina Fischer / Maroan el Sani

Toute la mémoire du monde - BNF I, 2006

C-Print, 124 x 150 cm

(statt Videostills der Videoarbeit)

Courtesy Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin and NGBK

© VG Bild Kunst, 2008

AH:

Let me add some other points to my colleague’s answer. First, we did

not commission any new works for this show, so none of these artists

intended on meeting our curatorial ideas; however, they were all very

delighted when we introduced our topic to them and invited them to take

part in the show. We did not want an exhibition where all the works

deal with all the same issues so we chose a variety of works, some more

narrative, others more associative and therefore interact with the

visitors in a more subtle and sensual way. We wanted to create a varied

response for our visitors so there might be works which are more

accessible, more readable than others – in the way of what they are

talking about - but there is this underlying unconscious access to art

and its topic, which functions best if you mix issues and formats with

each other. An exhibition is also a sensual parcours of understanding.

JS:

Do you think the cultural/political themes this show accesses help or

hinder the "healing" process for spaces that have been sites of

trauma/tragedy. How does one begin again and at what point is

this acceptable?

LB: A trauma -

individual or national based – that is not worked through and exposed

becomes a danger to repeat itself, or so teaches the psychoanalysis.

Ousted contents, painful or shame-related experiences should become

regarded, worked out and be integrated in the reality. I think using

artistic reflection, as a coping strategy, is a very good method and

one that contributes to the healing - and reconciliation process.

Oftentimes artistic expressions allow us to change our perspective by

actively trying to rehabilitate taboo themes and exposing questions

related to these taboos.

AH: To me this is a very complex question and I will try to comment with the example of the recently released film Baader Meinhof Complex

that has produced many heated and diverse discussions about this

question. The movie is about the terrorist group the RAF (Red Army

Faction) that was active during the 1970s, and which is still a subject

of national "healing". The German people have quite diverse and often

emotional reactions to what happened and are still interested in

finding out the truth. In the last ten years much better films on this

topic have been made but this new film is a so-called Blockbuster, an

entertainment film. So is it suitable to make a blockbuster film 30

years after this national trauma? I think this will motivate a dialogue

of dealing and healing in Germany.

JS: How

do you think the European Union is helping or hurting, for example in

countries with recent admittance such as Bulgaria and Slovenia, other

"Balkan" States deal with the history of these places?

LB:

I think that there is a discrepancy between the economic and cultural

integration of the new EU-states. For example, if states like Slovenia

or Bulgaria are economically integrated but yet are still in the

process of ongoing economic change this winds up creating further

cultural segregation from the rest of Europe. The related problems and

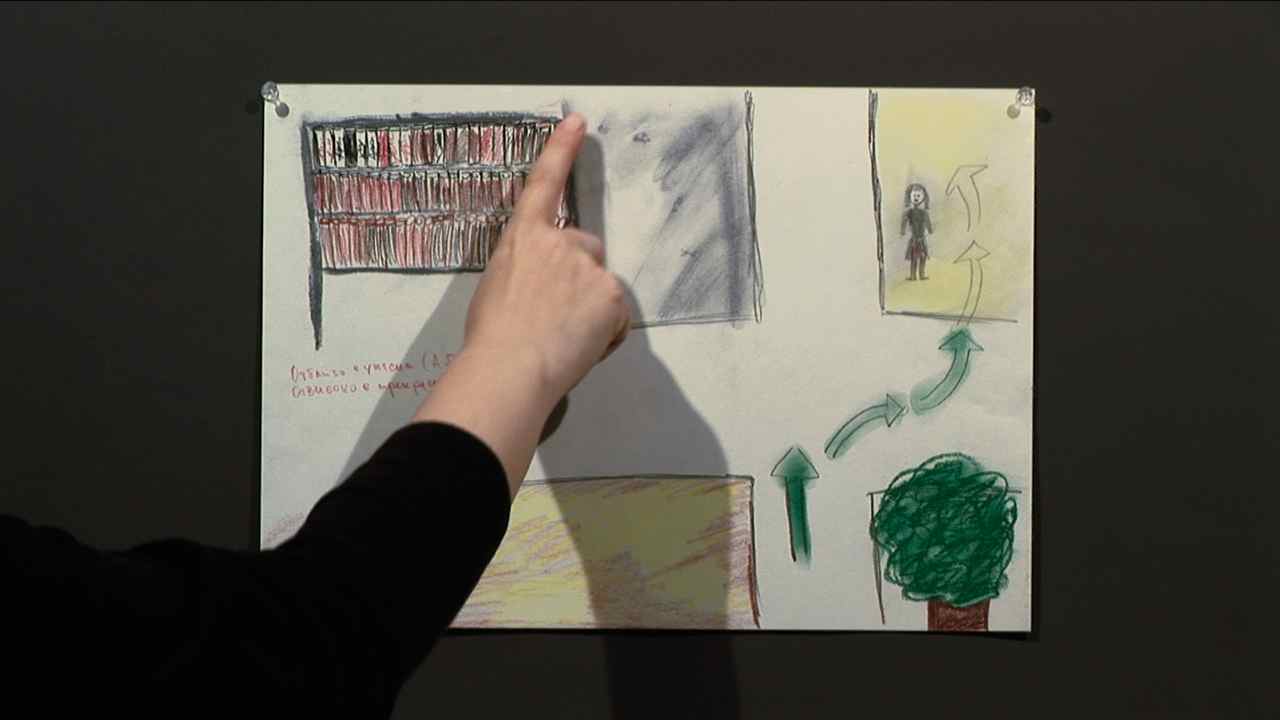

questions of identity are addressed by Ute Hörner and Matthias

Antlfinger in their multi-part installation Sofia Time Travel Experiment – Speaking with the unconscious social mind.

The artists used the methodology and ideas of American psychotherapist

Milton H. Erickson in order to study the sensitivities of

post-socialistic mentalities. He used the idea of mental time-travel to

enter into a dialogue with the unconscious mind, and thereby evoke

images from the past, and visions of oneself in the future.

In the recordings made by the artists, the protagonists mix

autobiographical memories with descriptions of the contemporary

historical phenomenon of the urban public space. This “oral history” of

the recent past and present in Bulgaria reveals hardly any bitterness.

Future-orientated visions reveal longings for safety, cleanliness, and

control and insecurities in the face of new social requirements. A

collective personal testimonial is expressed in the complexity of the

participants´ statements, a psycho- gram of the change of a social

system going beyond stereotypes and self-protectiveness. As opposed to

strategies of selective disremembering that one is often confronted

with when dealing with the post-socialistic past, psycho-social

practices used by artistic approaches may be capable of initiating a

subjective method of coping with the past, and a more interpersonal

exchange.

Hörner / Antlfinger

Sofia Time Travel Experiment – Speaking with the unconscious social mind, 2006

Fotos und Videostills

Courtesy of NGBK and the artists

© Hörner/Antlfinger

Hörner / Antlfinger

Sofia Time Travel Experiment – Speaking with the unconscious social mind, 2006

Fotos und Videostills

Courtesy of NGBK and the artists

© Hörner/Antlfinger

AH:

As Lith mentioned, the work of Hörner/Antlfinger gives a very

interesting insight into the souls of people in such a "transforming

city". We learn about their fears and hopes. The EU is a big step for

all these countries and combined with the hope to be "part of the

family" comes the disadvantages and disappointments. Therefore, I

think, in regards to whether the EU is helping or hurting a general YES

or NO is impossible to state.

JS: As

curators what is your role in this? does it fall into the

remembering or not forgetting? Where do you see yourselves in the

exhibition?

LB: At this point I would

like to mention the special and unique structure of our institution,

the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (New Society for Visual Arts)

in which members work together on different exhibition themes. In

addition to the changing project teams, a number of groups have been

engaged in more long-term continuous work. The development of our

concept preceded a discursive working process in the project group

RealismusStudio. The NGBK´s RealismusStudio has been in existence since

1973, albeit with changing personal. It addresses contemporary artistic

positions on current social questions. In this way, young, less

well-known and unknown artists, as well as internationally renowned

artists, enter into dialogue.

In this particular case of “the blind spot” my colleague Anke Hoffmann

and I did not have a prefab thesis to this project. Our point was to

follow a wide spread process of research which aimed to create a room

for reflection belonging to our questions on the topic of forgetting,

selective disremembering and memory repression. The result of our

research is visible in form of the exhibition, a catalogue and a small

number of events, including performances, a film- and video program and

some lectures. With all this we hope to inspire and make suggestions to

the visitors, to make them come closer to their own thoughts and

reflections on these themes.

AH: On both sides, naturally, thanks for your interesting questions.

| Jaime Schwartz is a freelance curator whose eye is lately focused on contemporary artists probing the uncertainties of contemporary urban life, especially those living and working in countries and cities undergoing abrupt transition. Jaime recently graduated with a Masters degree in Curatorial Practice and Contemporary Art Theory from San Francisco State University and is currently living in Berlin. While in Berlin Jaime enjoys admiring the mix of architecture and riding her bike in between studying German and working at AA- Galleries. jaimediamonds@yahoo.com |